The Silence

Enter

The Silence of War tells the story of a small group of African-American Vietnam veterans from rural, eastern North Carolina and explores how shared personal experience, the bonds of brotherhood, and the healing power of storytelling allowed these vets to break their years of silence.

This transmedia project, produced by faculty and students in The Imagination Project: The Silence of War at Wake Forest University, examines the theme of silence through aural, visual and graphic representations of place and intimate personal profiles that capture the mental and physical costs of war.

Ronnie Stokes

My time in the military made me realize that you could lose your life in a matter of a second. And it made me understand how sweet life is.

When I came off that plane, I dropped down on my knees on that tarmac and kissed it and I said I wasn’t ever going back.

My mama stood in the middle of the yard and said ‘Lord, what have they done to my son?’ They hadn’t done nothing to me, they just had scared me to death a couple of times.

Robert Lee Jones, Jr.

It was terrifying, but it was the honorable thing to do. So I did it. I have no regrets.

At eighteen, you are a kid. You are still a child. War is not something you understand. Until my first firefight, I didn’t understand how close we were to death.

The young folk need to know these things so they can have some impact on our laws and our politics such that eventually, hopefully, we can figure out how to do things without going to war.

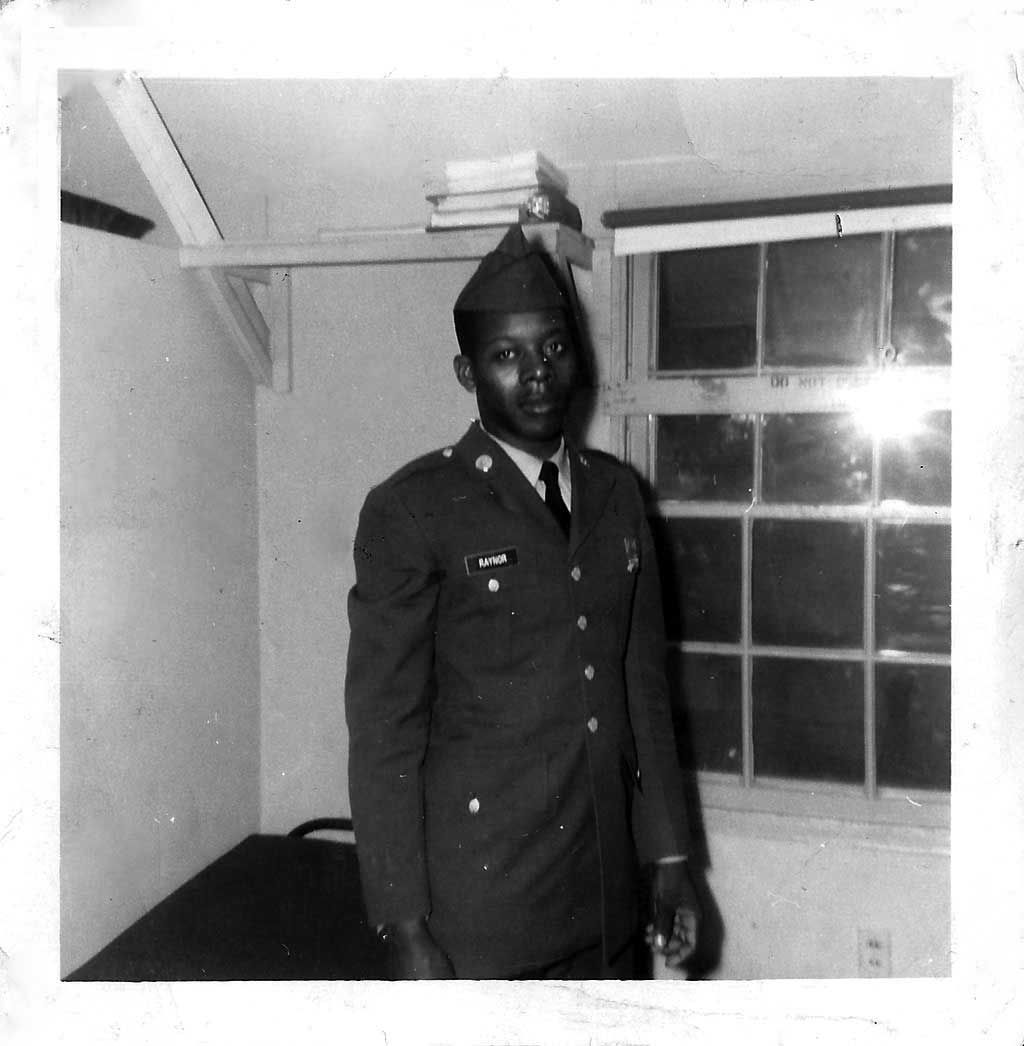

Louis Raynor

I looked at it like well, I’m just as good a man as anybody else and it’s time for us to do our job.

When I came back from Vietnam and [my brother] came back from Korea, all the years we never mentioned nothing about the military.... It’s just part of that other life that we just shut out.

I kept to myself and didn’t want to talk to nobody and didn’t want to deal with nobody. It’s really hard to explain, but it’s like something you want to get out of but you can’t.

John Barnes

I just wanted to get away from home. And it worked out. I got away from home. But when I got there I wanted to be back home, so I don’t know whether that worked out in my favor or not.

After I got out of the Army, I had probably been home a month. All the clothes and stuff I had in my duffel bag. I just burned it. I didn’t want to have no memories of it. I just burned everything.

But it didn’t work out. I still remembered.

Ralph Shaw

I think sometimes maybe I – should have shared more but I couldn’t. Well, who wants their kids put up with other kids talking about how your daddy is crazy, he served in Vietnam.

They debriefed us that when you got back to the States, you might get spit on or something. And the spit on is what caught my mind because I hadn’t worn my dress uniform for 19 months. And for somebody to spit on my uniform, it wasn’t just the fact that they were spitting on me but they were spitting on my uniform.

If you ever put the uniform on, you’re never a civilian again because there is going to be a part of you that goes with that uniform every day.

Charles Helbig

When I came back from Vietnam, I stayed busy. Stayed busy to escape my memories.

I didn’t talk about it, for years, I didn’t talk about it because it was classified. We took an oath so I didn’t say anything.

You do what you have to do.

John Nesbitt

I had in my mind that, I’m going back home, I’m going to get back and, if I can, I’m going to carry these guys with me.

I try not to get close to people. I think I’m going to lose them somewhere along the line and I can’t take that anymore.

Tex Howard

Your whole outlook on life changes. You have fears you don’t even realize you have. I guess because you are possibly facing death and not knowing the outcome. And it changes you.

When it comes to addressing your experiences in Vietnam, you get the feeling that the public doesn’t want to hear about it. And I don’t want to tell them.

Everyone wants to be appreciated. And I’m not saying that what I did no one had ever done before. But I’ve done something that should put me equal to any other man. But it didn’t. And I had to accept it. You suck it up and you drive on, we used to say in the military.

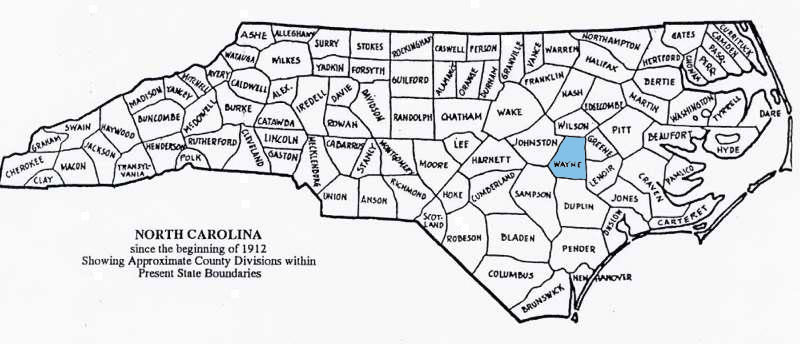

Life Before the War

A glimpse into rural eastern North Carolina farming history and life before the Vietnam War for local sharecroppers

Tex Howard, Ronnie Stokes, and Louis Raynor all fought in the Vietnam War and all have one thing from their past in common: they grew up in the rural south in families of sharecroppers. Their lives before the war are all similar and they express some interesting facts about the life path of a sharecropping family. Many of them had only one option out of their hometowns: joining the fight in Vietnam.

Sharecropping - a system of farming in which landowners permit tenants to use the land in exchange for a portion of crops grown.

Most Grown Crops in 1960s North Carolina:

Tobacco, Peanuts, Cotton, Corn, Wheat

Income Facts -1960

- Average Household Income: $4,816

- 1 Gallon of Milk: $0.95

- Movie Ticket: $1.00

- Gallon of Gas: $0.31

- Price of a House: $21,500

Vietnam:

A Timeline in Pictures

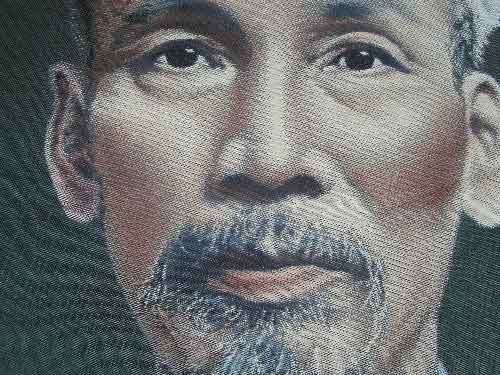

At the end of World War II, Vietnam fights to overthrow its French colonial rulers and establish itself as a communist republic under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh.

The Geneva agreement of 1954 divides the nation into temporary halves. The U.S. supports the South. The Soviet Union and China support North Vietnam.

A number of factors contribute to U.S. anxiety about the spread of communism.

The Soviets test a nuclear bomb.

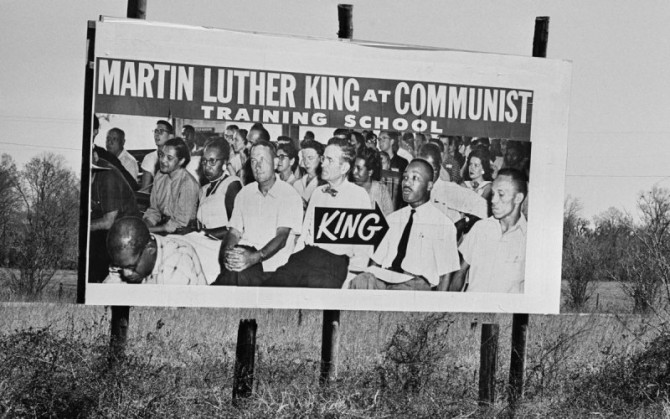

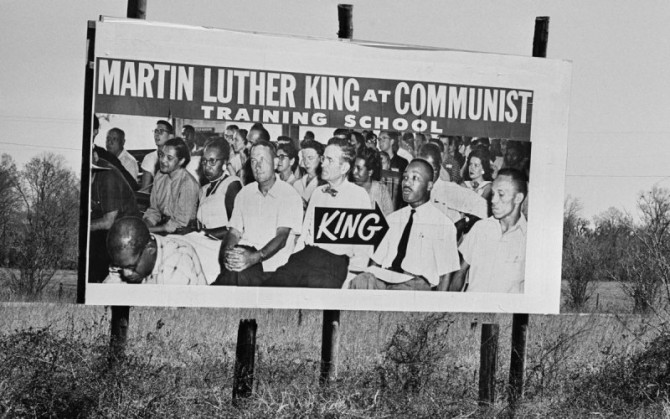

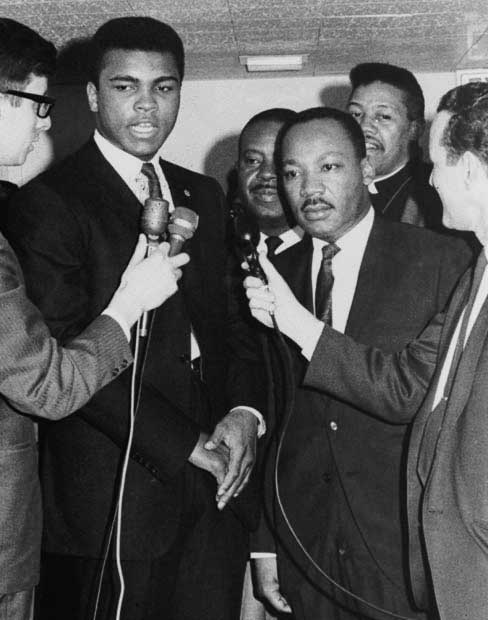

The House Un-American Activities Committee calls Langston Hughes and other prominent African American figures to answer questions concerning their communist affiliations.

Segregationists in the south frequently label civil rights activists as communists.

“I’m not talking about communism. Communism forgets that life is individual. Capitalism forgets that life is social. And the kingdom of brotherhood is found neither in the thesis of communism nor the antithesis of capitalism, but in a higher synthesis.”

Martin Luther King Jr.

The war starts slowly.

The U.S. forms MAAG, the Military Assistance Advisory Group, to advise the South Vietnamese government.

The official start date of the Vietnam conflict is November 1955.

The Civil Rights Movement proceeds on several fronts.

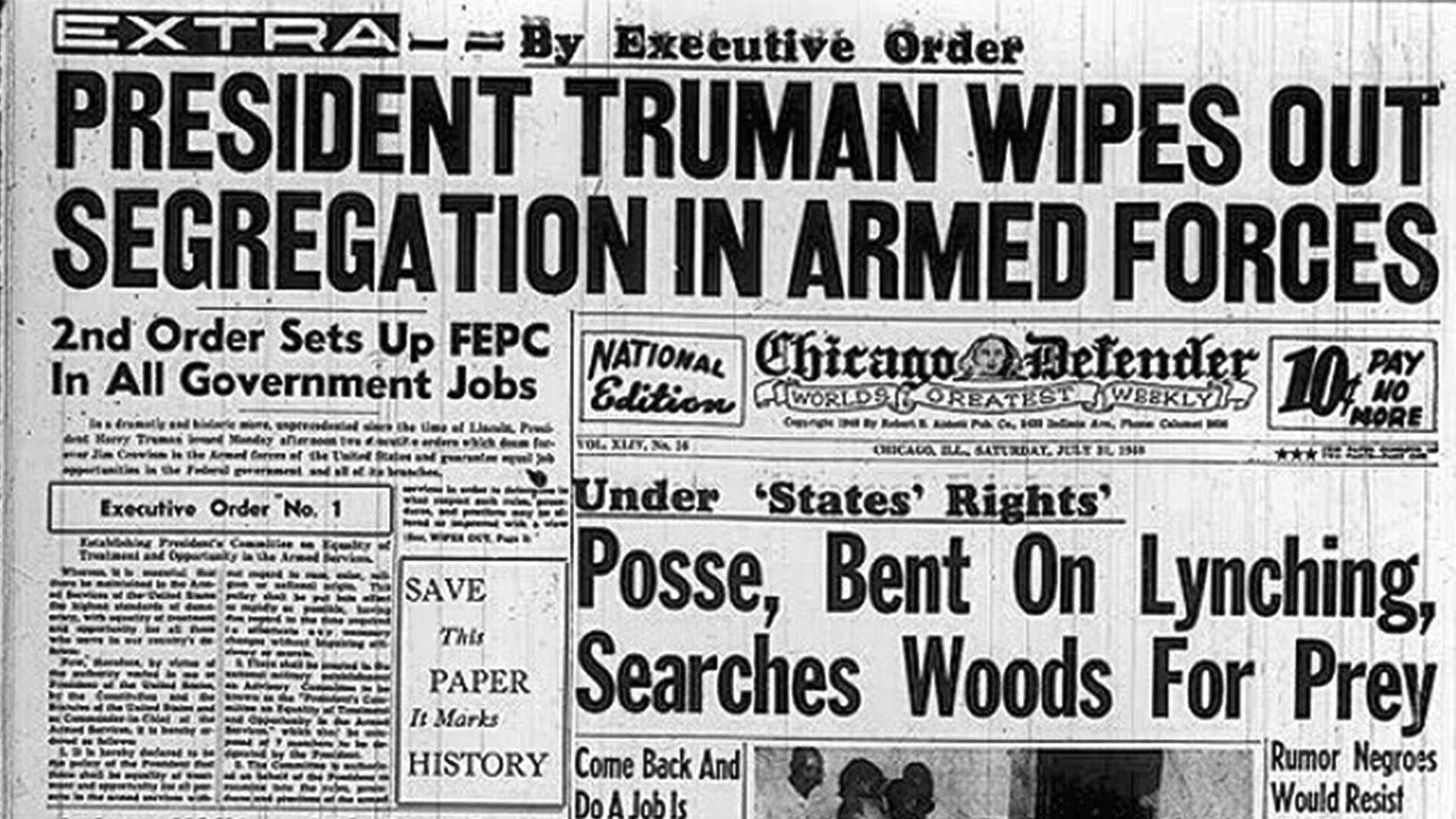

President Truman issues an executive order that desegregates the U.S. Armed Forces.

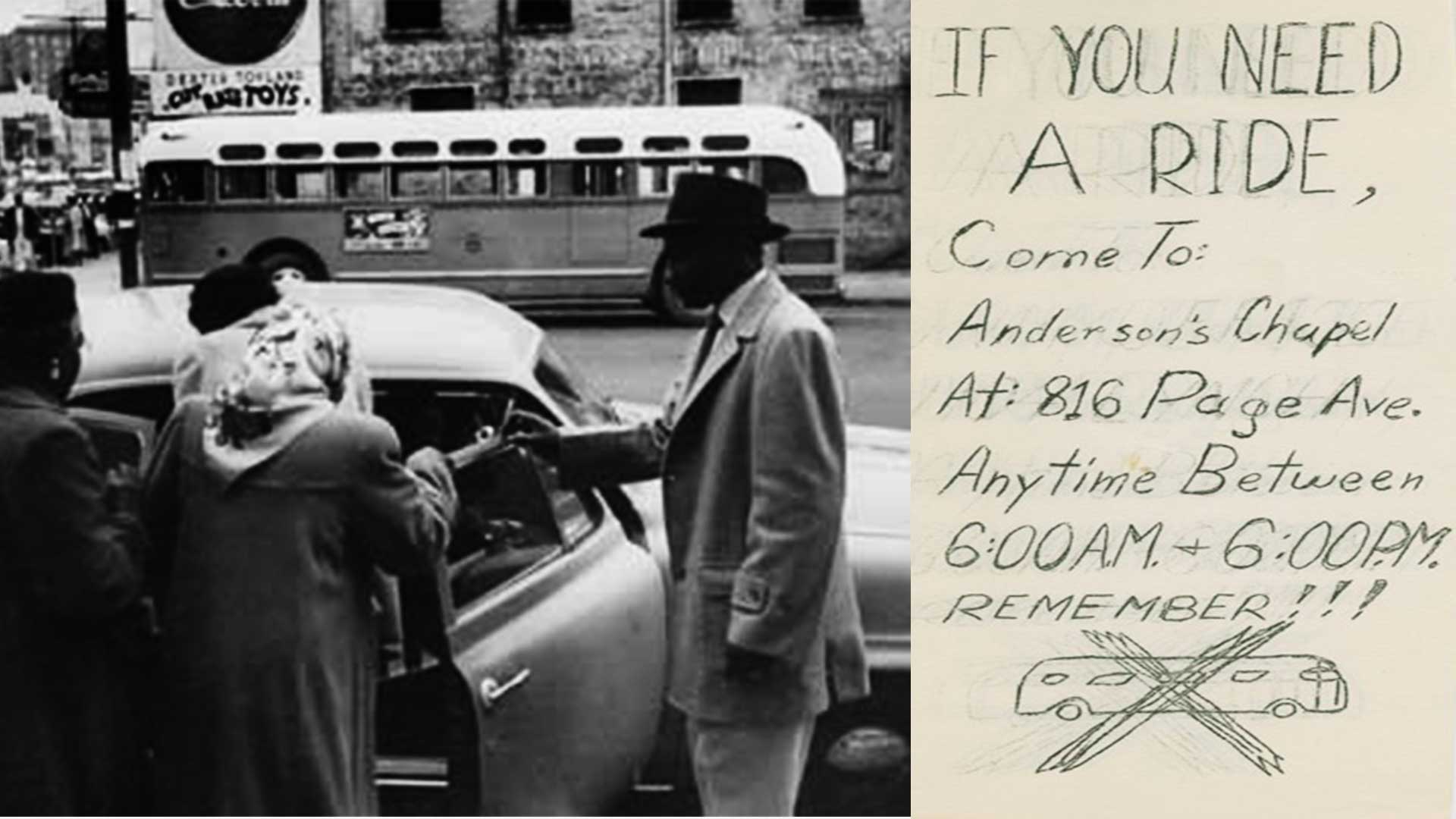

The Montgomery Bus Boycott.

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense Fund team wins the 1954 Brown vs. The Board of Education decision.

The February 1st Greensboro sit-ins launches a nationwide protest movement. By the end of April, over 50,000 students sit in at 30 locations in seven states.

Operation Hades, later renamed Operation Ranch Hand, begins aerial spraying of herbicides, notably Agent Orange, to defoliate the jungle.

By the end of the war, the U.S. military sprays some20 million gallons of Agent Orangeand other herbicides across Vietnam and some parts of Laos.

AP.jpg)

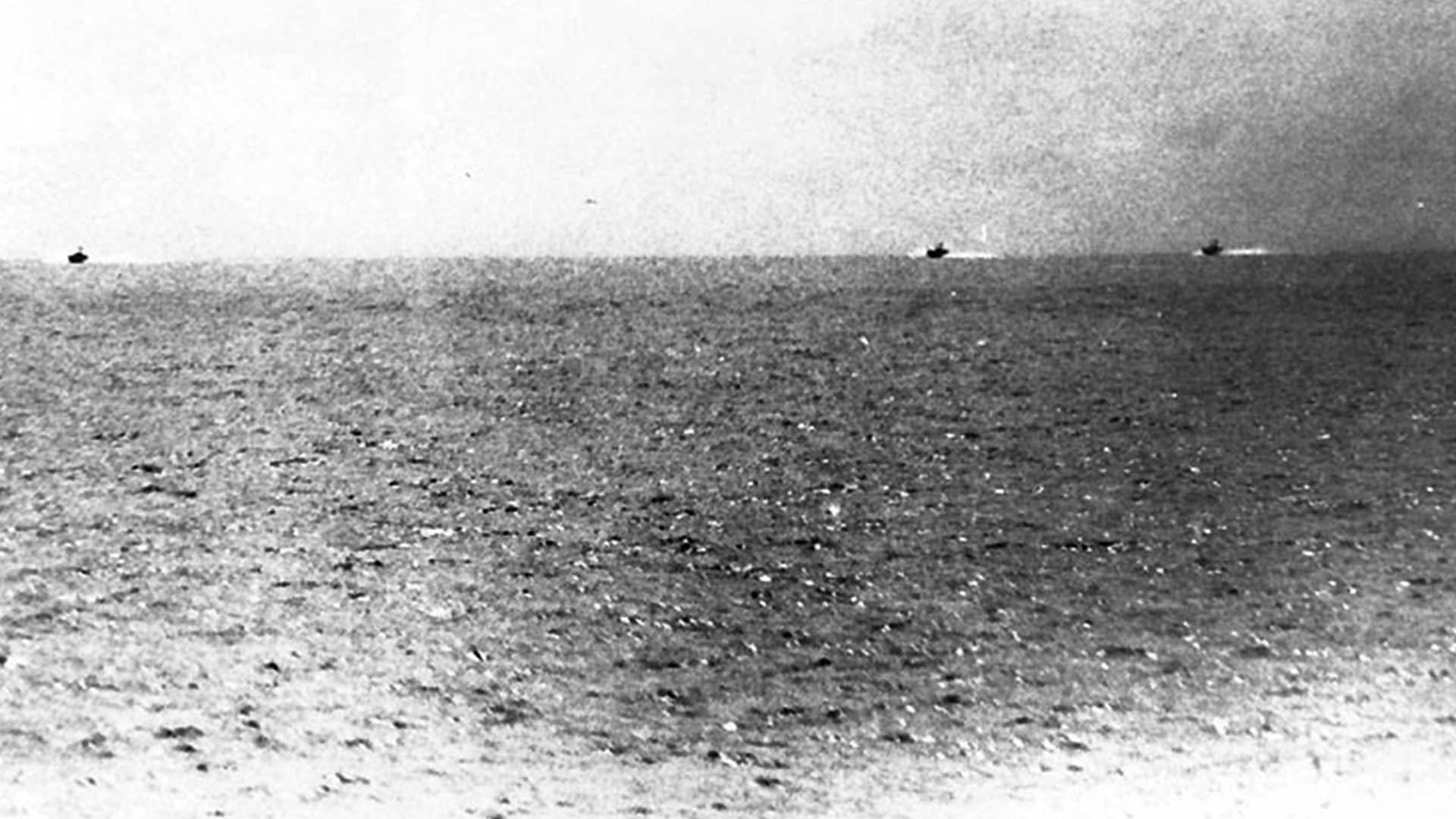

August 2nd

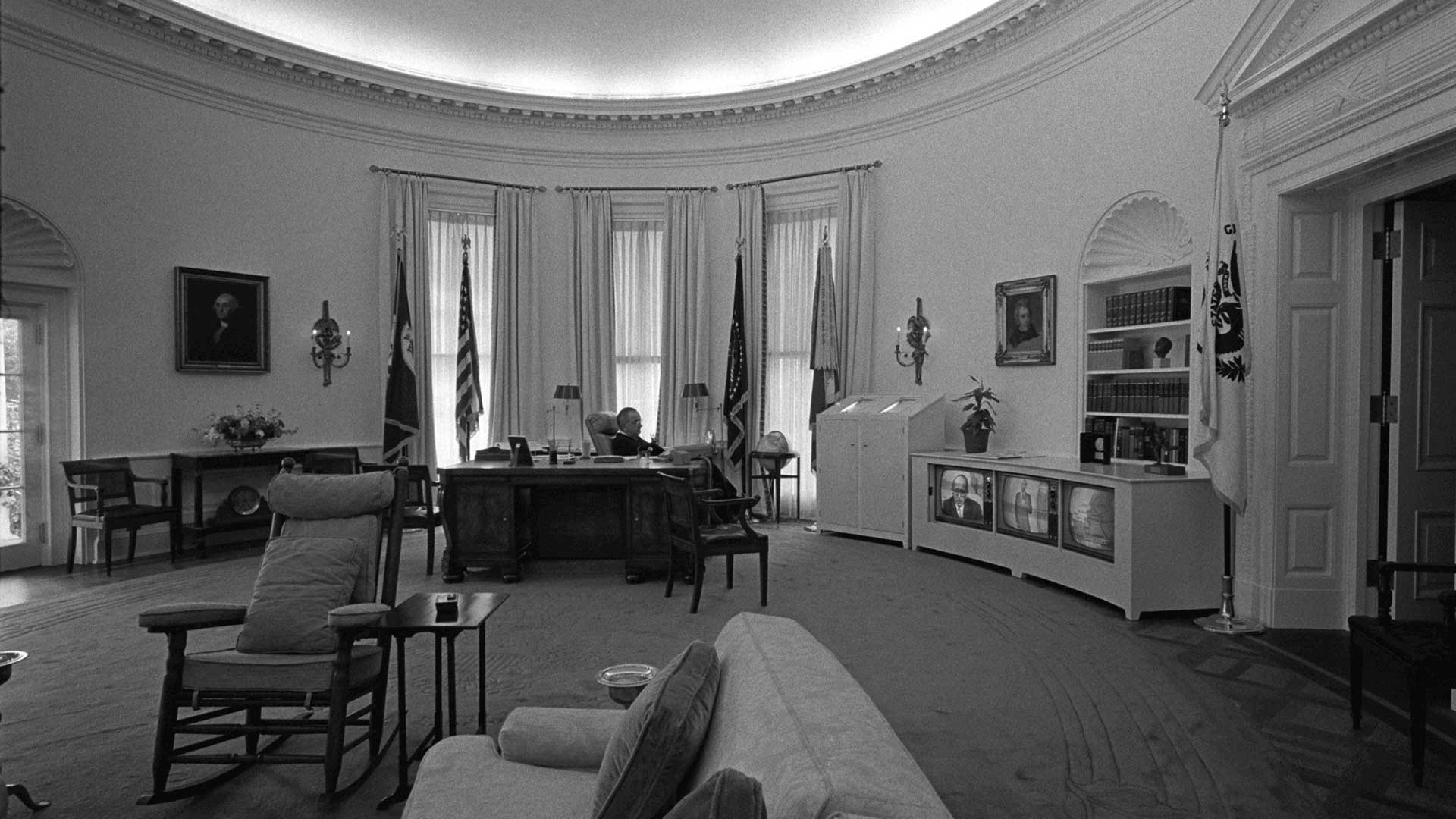

Provoked by “aggressive intelligence-gathering maneuvers” three North Vietnamese torpedo boats attack the U.S.S Maddox. Johnson uses the battle as a pretext to escalate the war.

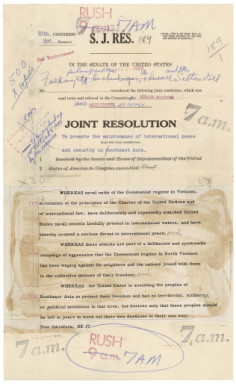

Congress passes the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that allows President Johnson to use any measures he believed necessary against North Vietnam.

AP.jpg)

President Johnson launches the first major bombing campaign, Operation Rolling Thunder.

Students in New York City burn their draft cards.

Draft card burning becomes a powerful symbol and frequently used form of protest against the Vietnam War.

AP photo.jpg)

March 8th. The first ground troops, the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, arrive in South Vietnam.

By 1965, the majority of Americans get their news via television. Graphic reports from the front line will help turn public opinion against the war.

Frank Stanton, CBS president, receives a call from President Johnson regarding the Cam Ne report.

"Frank, are you trying to f– me?"

"Who is this?"

"Frank, this is your president and yesterday your boys shat on the American flag."

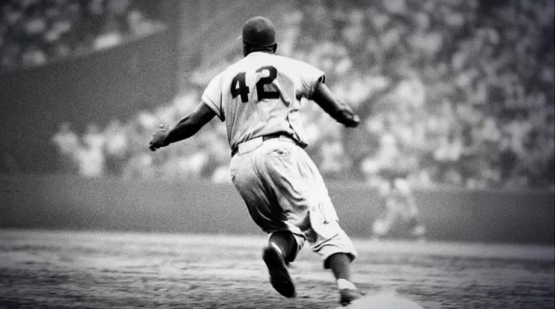

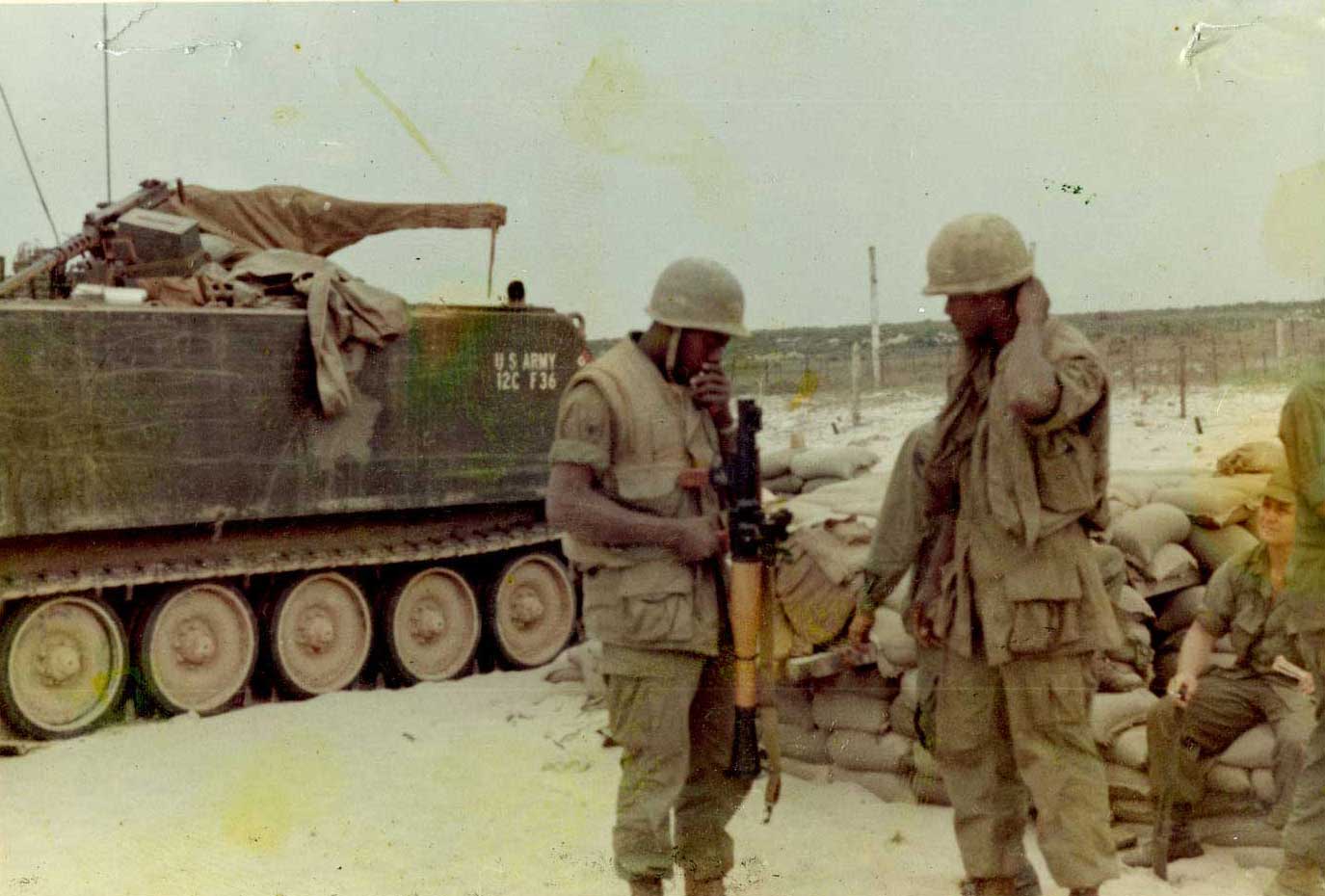

Between 1961 and 1966, African Americans accounted for almost 20 percent of all combat-related deaths in Vietnam.

They made up less than 10 percent of American men in arms and about 13 percent of the U.S. population.

This is an excerpt from a 1967 speech, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence,” at Riverside Church in New York.

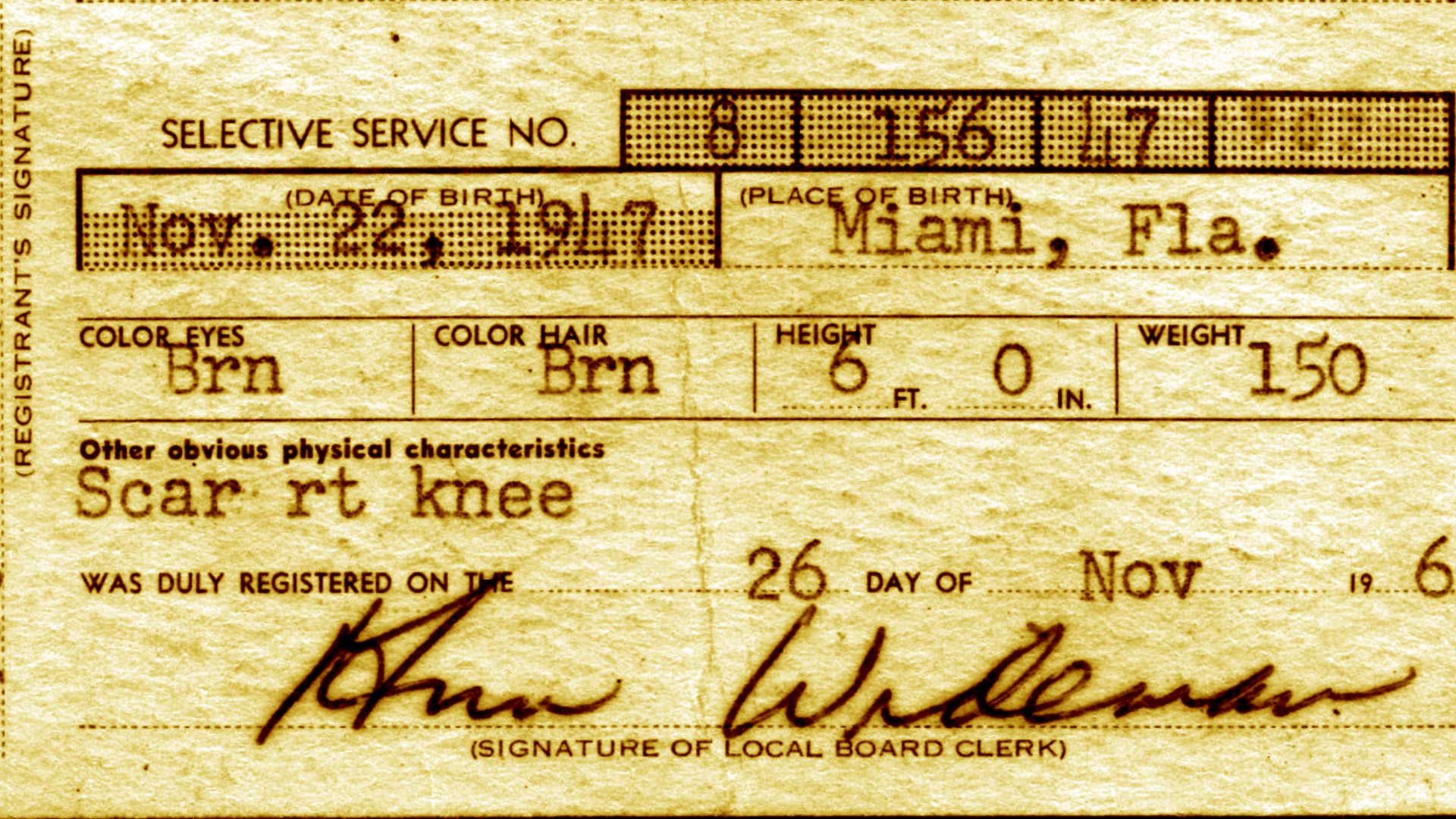

April 28, 1967: Muhammad Ali refuses Army induction on the basis of being a conscientious objector.

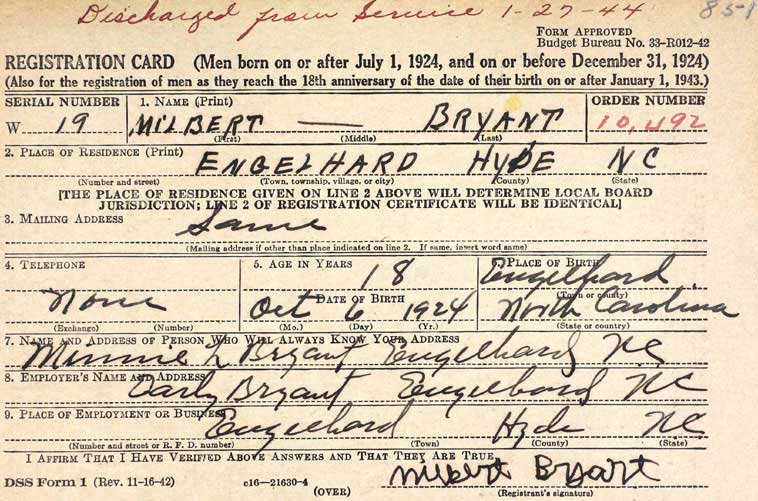

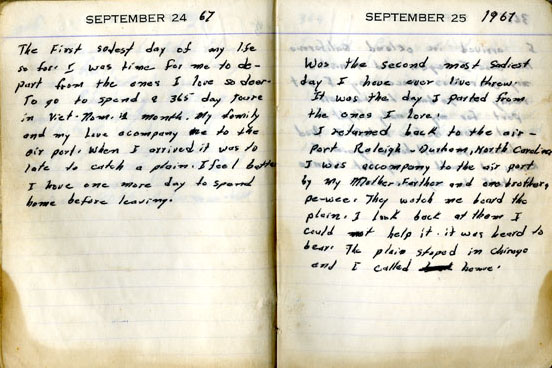

(from the diary of Louis Raynor)

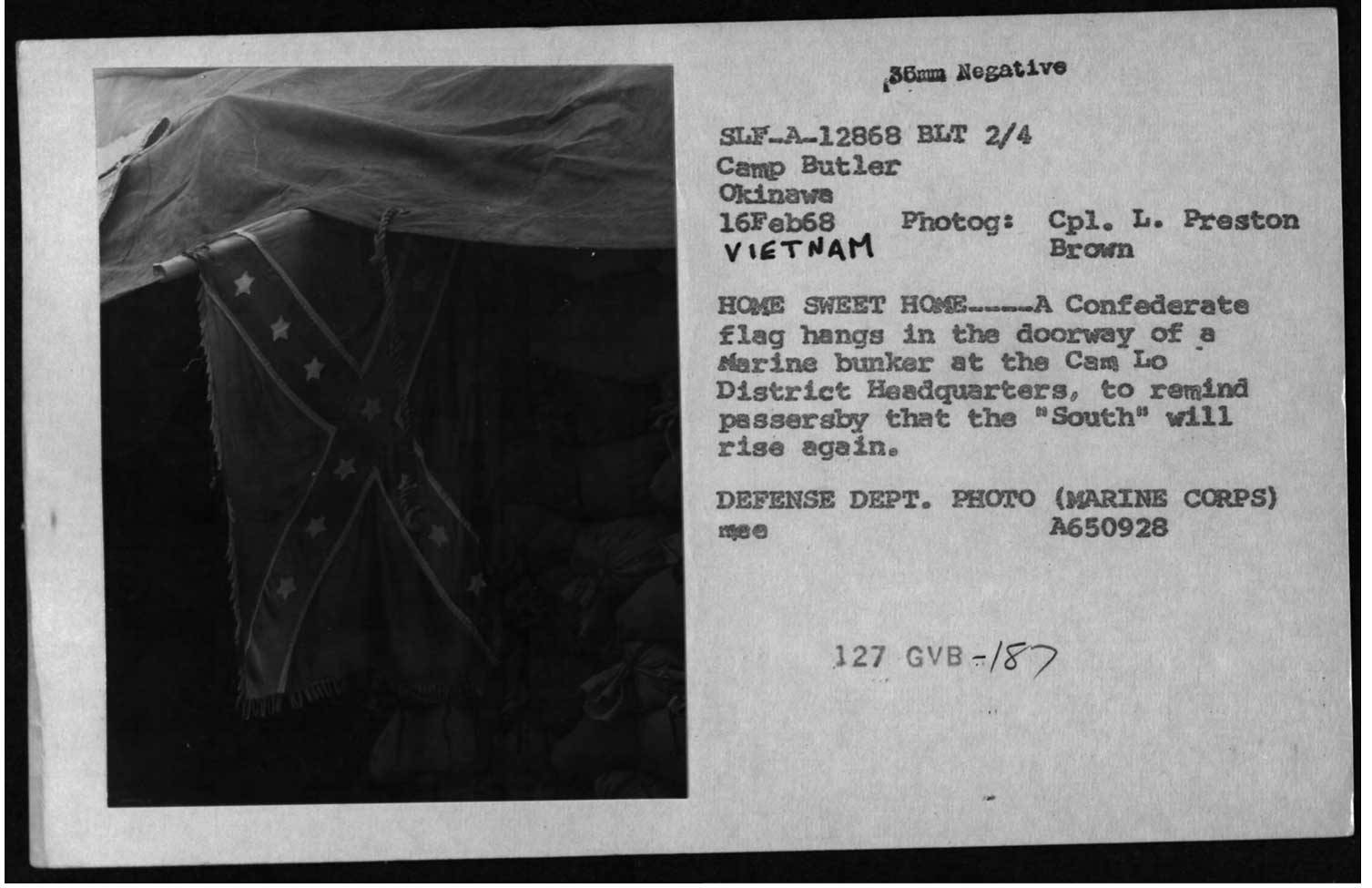

There are numerous reports of racial incidents including beatings, riots, fragging, cross-burnings and displays of the Confederate battle flag. Black soldiers are more likely to receive severe discipline, including court marshals and dishonorable discharges.

In 1965 alone, almost one-fourth of the Army’s troops killed in action are African American.

“Southerners who came under control of a black officer being in charge of them were somewhat reluctant. But then, when they found that you know what’s going on and you’re trying to keep them alive, then they tried to be the best damn soldiers you’ve got.”

Archie “Joe” Biggers - Platoon Leader

As quoted in the book Bloods by Wallace Terry

In 1968, African Americans, who make up roughly 12 percent of Army and Marine service members, frequently comprise half the men present in front-line combat units, especially in rifle squads and fire teams. men in front-line combat units, especially in rifle squads and fire teams.

The Vietnam Moratorium Committee staged the largest antiwar demonstration in U.S. history.

The November 15th Moratorium March drew half a million demonstrators.

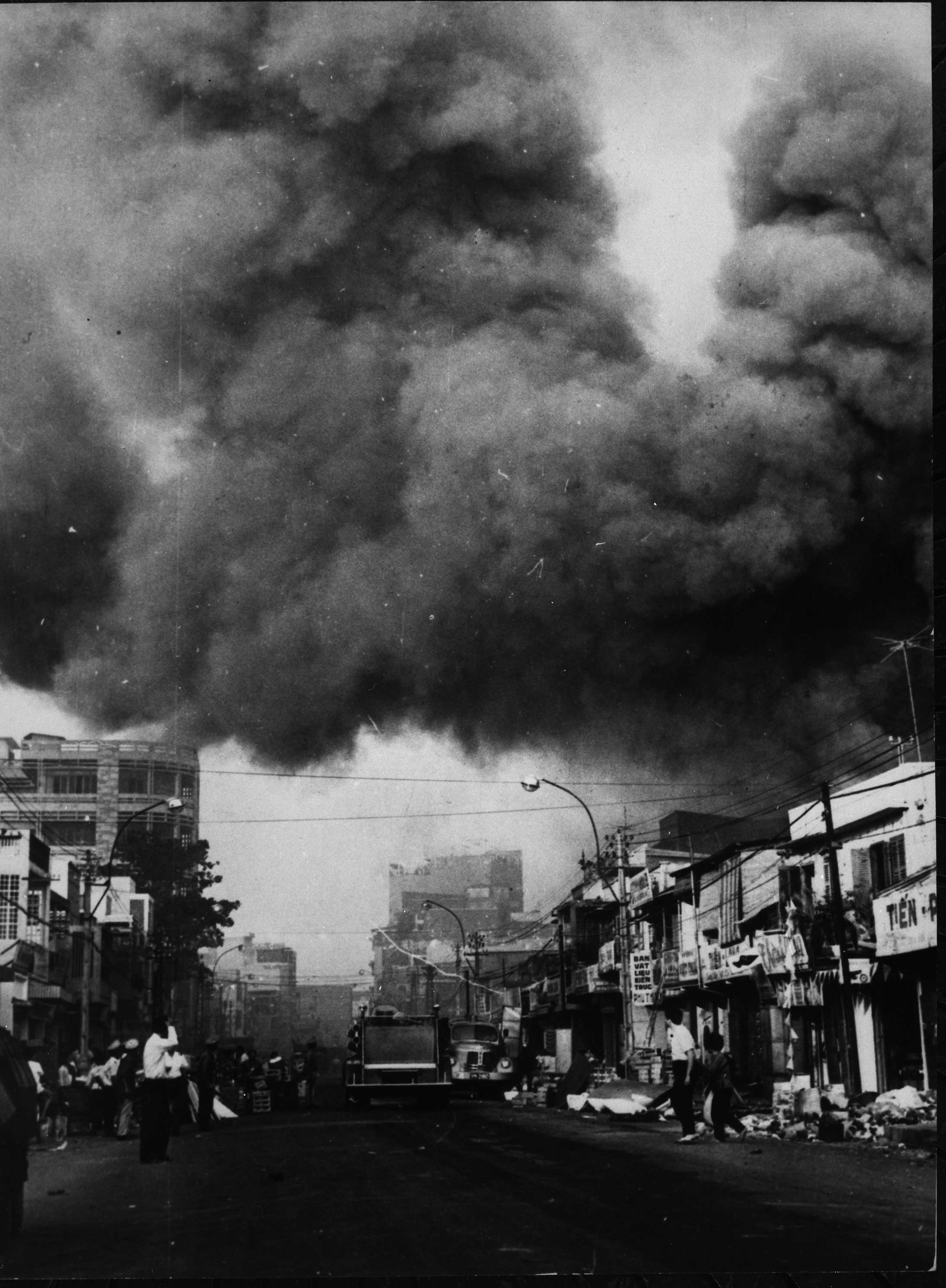

The North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong launch a surprise attack during the Vietnamese New Year celebrations.

News of the bold coordinated attacks shock the American people and President Johnson, who had been told that the U.S. was winning the war.

The offensive is a military failure, but a major propaganda victory for the North Vietnamese.

It proves to be a turning point in the conflict. In March, Johnson begins looking for ways to disengage from the war.

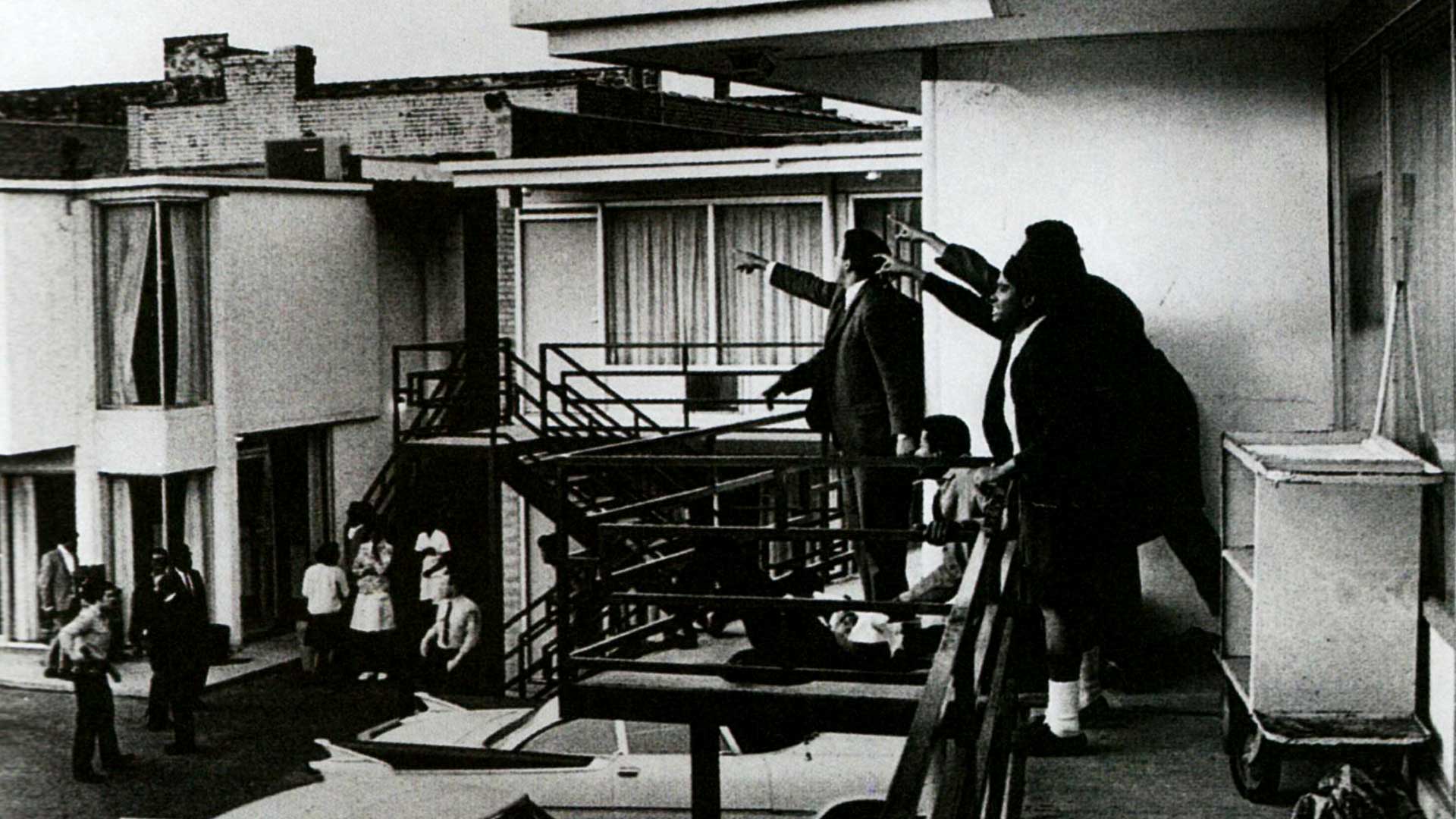

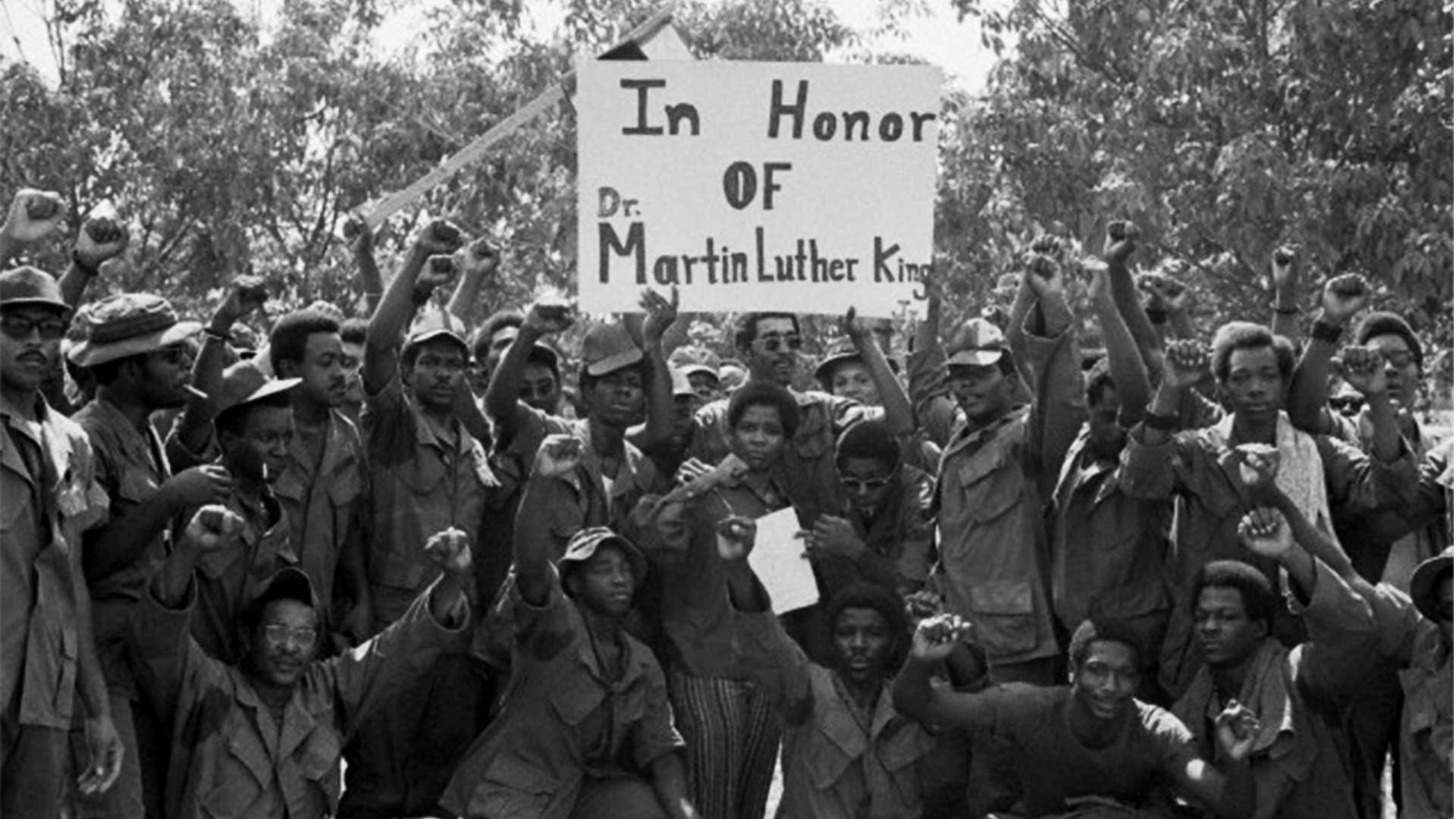

Martin Luther King Jr. assassinated

April 4th, 1968

Rioting broke out in 110 cities.

When news of Martin Luther King’s assassination reaches Vietnam, some white soldiers and officers hold parties to celebrate.

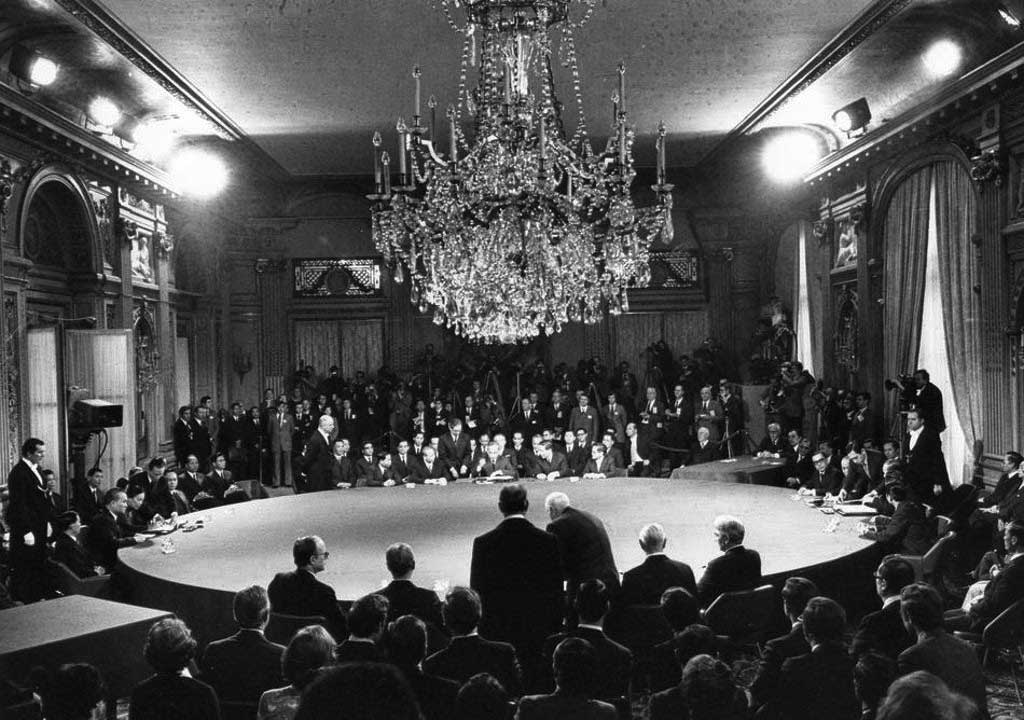

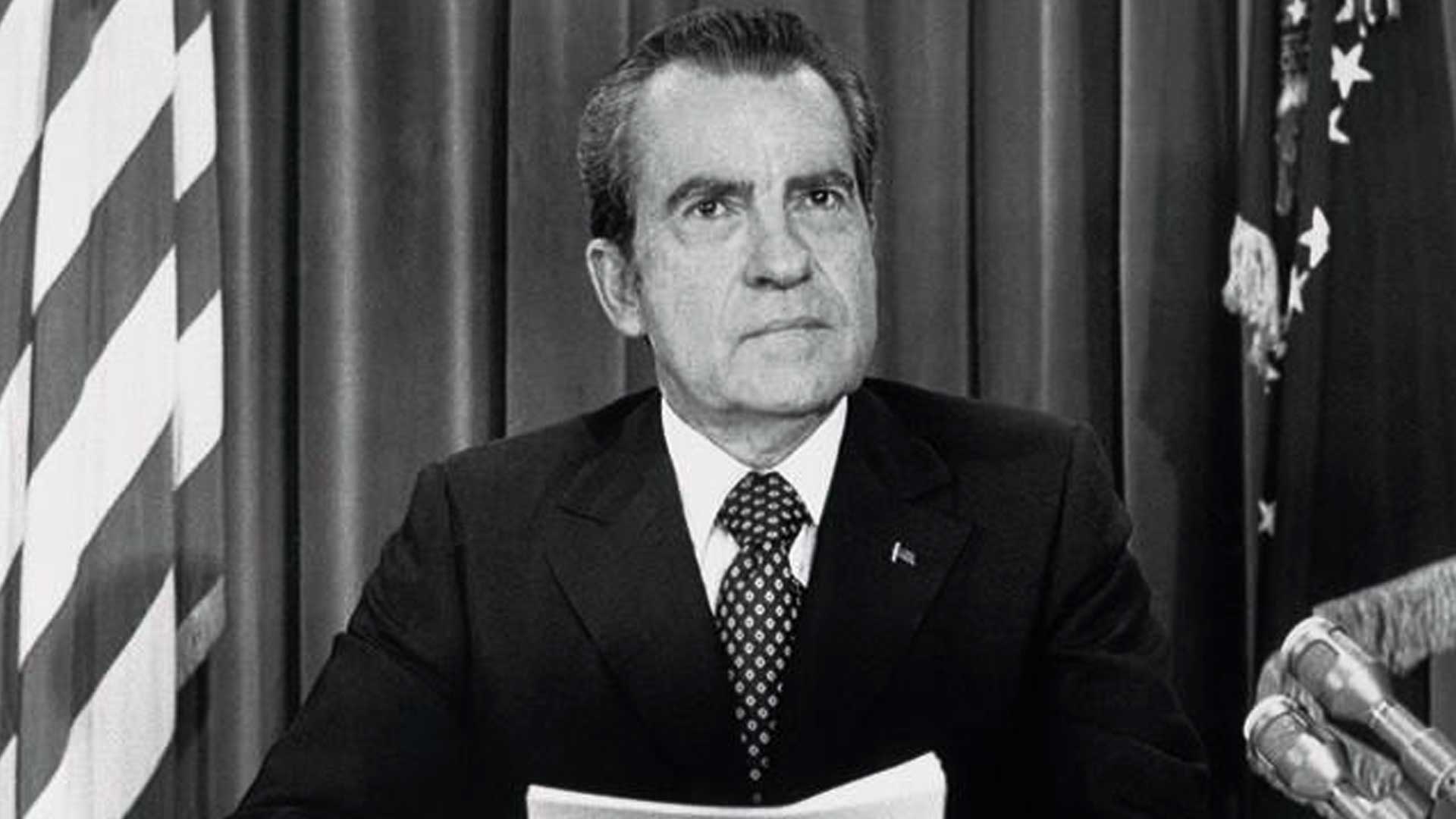

Jan 28th 1973. The United States and North Vietnam sign, “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam.”

Nixon: "We had won the war in Vietnam. We had attained the one political goal for which we had fought the war. The South Vietnamese people would have the right to determine their own political future."

The U.S. withdrawals from Vietnam, brings home the last combat troops in 1974.

Over the course of the war the imbalance of enlisted men and fatalities moved in the direction of parity.

12.5% (7,241) were black.

Overall, blacks suffer 12.5% of the deaths in Vietnam at a time when the percentage of blacks of military age was 13.5% of the total population.

The war ended when the North Vietnamese army captured Saigon. Diplomats, U.S Marines, several thousand Americans living in Vietnam after the cease fire and numerous of South Vietnamese scrambled to leave the country by helicopter.

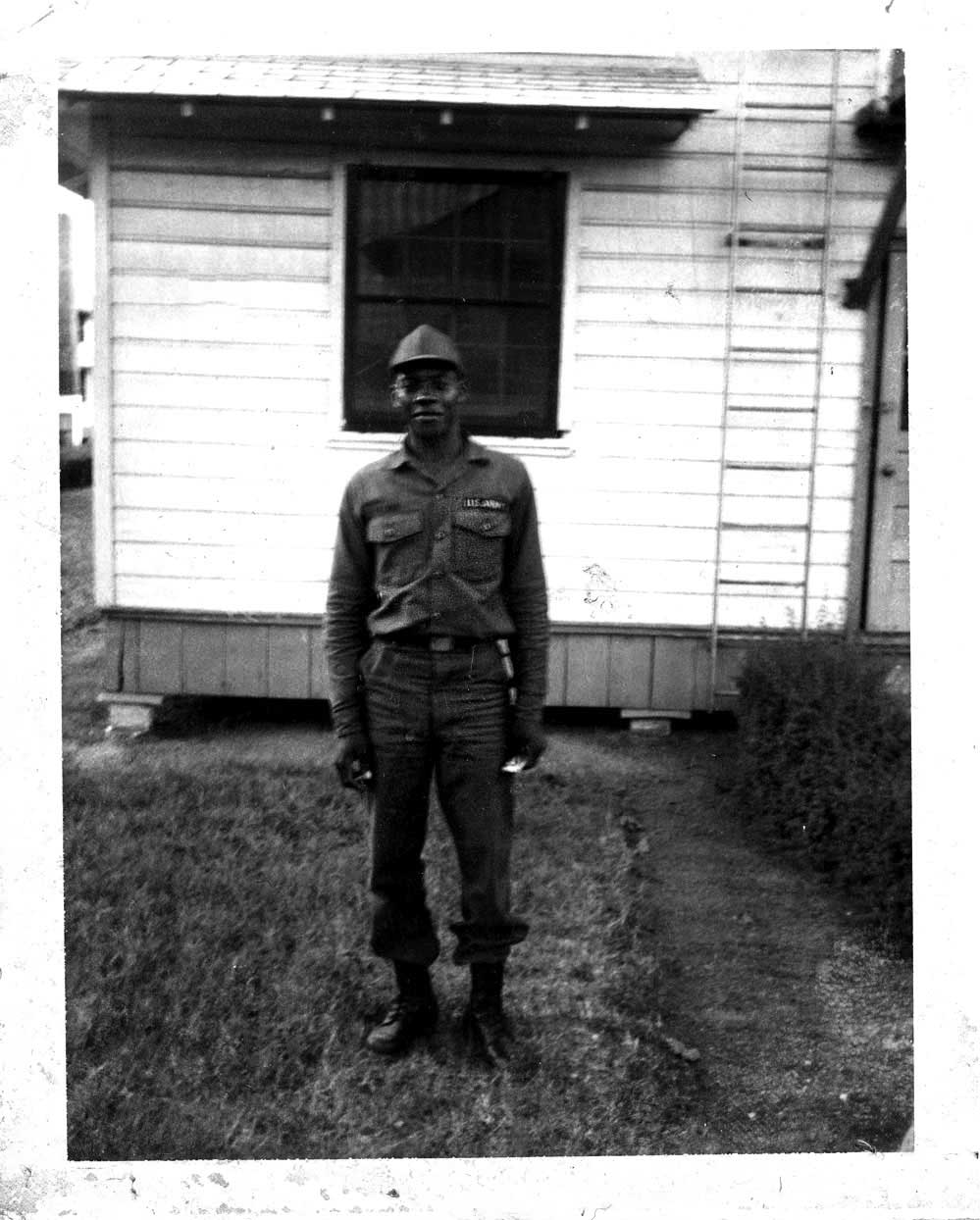

Private John Barnes

At the age of eighteen, John Barnes joined the Army to escape rural North Carolina. Over the course of his yearlong deployment in Vietnam, Private Barnes served in the 1st, 9th, and 25th Infantry Divisions. For his service, he received numerous awards including the National Defense Medal and Combat Infantry Badge. This video is a snapshot of his visceral experience.

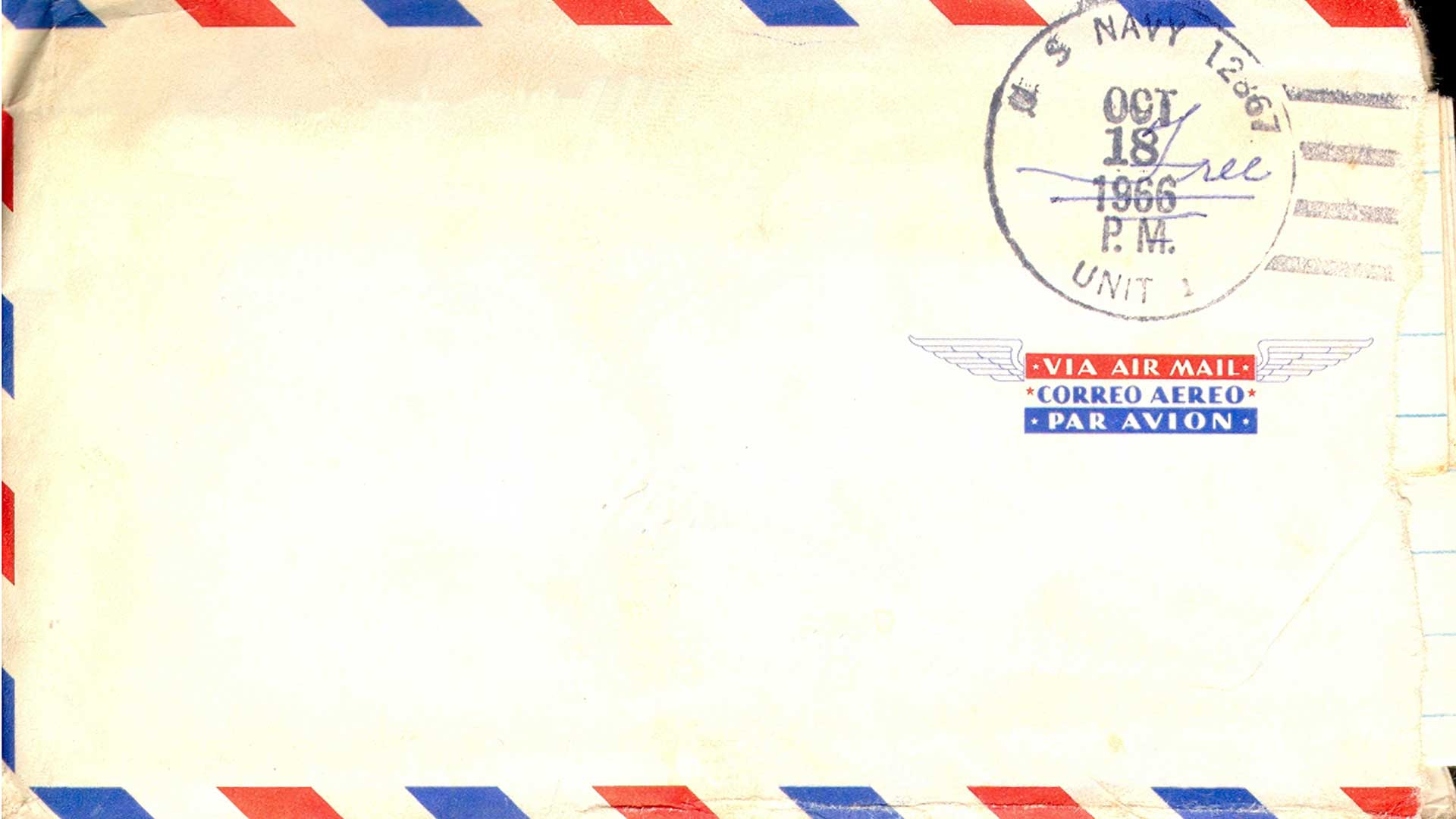

Lifelines

‘Lifelines’ highlights the experiences of John Barnes and Ronnie Stokes, focusing on life outside combat during the Vietnam War. Through this collection of interviews, Barnes and Stokes recall their memories of the letters they received, the food they ate, and the music they played in order to maintain a connection to one another as well as friends and family back home.

Navigating the VA

A Family's Struggle

The purpose of the Veterans Administration is to recognize and assist those who have served the country, but the complexity within the VA often prevents veterans from getting the benefits they deserve. Veteran Louis Raynor has suffered from a multitude of health problems as a result of his service in Vietnam. For Louis, his wife Katie, and their daughter Sharon, fighting the VA to obtain these benefits has become a family affair. While the VA has improved since Louis first started going, needless obstacles and inefficiencies continue to challenge them. This piece focuses on the Raynors and their fight to ensure Louis gets the health care and disability compensation he deserves, which has been a big part of their lives since Louis returned home from Vietnam.

We would like to thank Louis, Katie, and Sharon Raynor for their participation and their willingness to share their story. Furthermore, we admire their determination and perseverance to never give up despite their struggle and frustrations with the VA.

Brotherhood

It's been said that time heals all wounds, but traumatic experiences have a way of keeping them open. The men who fought in Vietnam, however, have a stronger weapon: sharing stories, displaying kindness and being Brothers to one another.

Devoted

a Tribute to the Wives

by Abriana Kimbrough

Devoted

by Abriana Kimbrough

“But I’ll go home someday and when I do, a new life I’ll start and I‘ll be glad I did my part.”

These were his words, like blood from his wounds

They spilled from his heart.

They gave him a little ounce of hope,

Only to find that when he woke

His dream was not his reality

He was silent and his life far from where he imagined it.

“When you come out of the military you’ll have a different man than what you had when you went in there.”

Now this, this was their reality.

The man she married vanished like the dust of those bodies

He was murdered by their words

baby killer repeated over and over like shots in the night

yet she tried to speak life into him resuscitate him through her light

His body stayed cold, he ran from his soul, He was silent

What kind of woman was she to take all the back-lash?

She is strong and sophisticated, not easily shaken

Loyal to him then, still devoted to him now

But not even a gun could make him sound

She remained hopeful…she remains hopeful

Sacrificed it all to lift him from the foxhole

“seemed like a better way of living was going to the military.”

OH but that was then, now look at them now.

Everyday seems like an uphill battle

While he disappears in the dark

she is left on the frontline

Hoping that victory will appear during the sunrise

Fishing with Tex

An interview with Tex Howard at Seaview Fishing Pier, North Carolina, Oct. 15, 2015.

Part 1 of 3: Sharecropping Before the War

Tex talks about his life as the son of a sharecropper in rural North Carolina. He explains why he joined the military.

Part 2 of 3: Trauma and Silence

Tex recounts experiences from Vietnam including a traumatic injury. He reflects on why veterans don't like to talk about their traumatic experiences.

Part 3 of 3: Racism and Terror

Tex discusses the ongoing terror caused by racism. He describes how he felt as an African-American soldier fighting for a country with deep racial prejudice.

Breaking the Silence

As a young girl growing up in Clinton, North Carolina, Sharon Raynor was curious about her father’s experience in Vietnam and even more curious as to why he would not talk about it. Years later, the questions left unanswered by her father would lead her to embark on an oral history project with the goal of breaking the silence of Vietnam veterans.

About This Project

The Silence of War builds upon the work of Sharon Raynor and explores the relationship she forged with a small group of veterans in Eastern North Carolina while collecting oral histories on trauma and the Vietnam War. Raynor, an Associate Professor of English at Johnson C. Smith University, has devoted 20 years to working with Vietnam War veterans in North Carolina and has written and directed two oral history projects sponsored by the North Carolina Humanities Council titled "Breaking the Silence: The Unspoken Brotherhood of Vietnam Veterans," and "Soldier-to-Soldier: Men and Women Share Their Legacy of War."

The site was produced by students and faculty in The Imagination Project at Wake Forest University. The Imagination Project brings together graduate and undergraduate students from various disciplines to explore visual storytelling and transmedia approaches to subjects with a liberal arts and humanities focus. Over the course of a semester, the students studied the Vietnam War, met with Sharon Raynor and the veterans to collect their stories, created the framework for the site and produced materials that examine the theme of silence and the trauma of war.

We thank Sharon, and all the veterans involved, for starting this journey and sharing it with us. The experience of working on this project was transformative for the faculty, the students and the veterans.

Site Credits

The Vets

Geoff GrobergSarah Fahmy

Life Before the War

Olivia DubendorfHarmony Morkve

Map

Scott SchimmelPrivate John Barnes

Alex FaoroJohn Gallen

Jasmine Luoma

Lifelines

Merritt PeeleAndrew Rose

Wei Ying

Navigating the VA

Drew CowanAnne Campbell Crockett

Kristy Smith

PTSD

Cynthia HillCara Pilson

Brotherhood

Brian GerstenJoshua Harris

Luke Kohler

Devoted: A Tribute to the Wives

Abriana KimbroughFishing with Tex

Geoff GrobergBreaking the Silence

Cynthia HillCara Pilson

Race and War in Pictures

Joe JowersScott Schimmel

Ben Smith

Photography

Geoff GrobergScott Schimmel

Joe Jowers

Luke Kohler

Drew Cowan

Archival Materials

John BarnesNorth Carolina State Archives

National Archives

Louis and Katie Raynor

Sharon Raynor

Psychedelic Shack

Written by Barrett Strong/Norman WhitfieldPerformed by The Temptations

Courtesy of Motown/Universal Music Group

Web Programming and Design

Geoff GrobergThe faculty and students in The Imagination Project: Silence of War wish to thank the veterans and their families for their service and for their participation in this project

John and Sharon Barnes

Charles and Marie Helbig

Tex and Joann Howard

John Nesbitt

Robert Lee Jones, Jr.

Louis and Katie Raynor

Ralph Shaw

Ronnie Stokes

Produced with the support of the Documentary Film Program and The Humanities Institute, Wake Forest University.